Let us look at three thoughts which are at the forefront of economic policy. There is a high level of urgency to ensure that the Indian economy hits the $5 trillion mark, which is around ₹415-420-lakh crore. Going by the Budget, it is slated to touch ₹328-lakh crore for FY25. The $5 trillion mark should be achieved in FY28 quite comfortably, if not earlier. Further, as the next aspiration is to cross the $7 trillion mark, this should be achieved by FY31 assuming growth in nominal GDP of 11-12 per cent per annum on an average.

On the other side, the government seems determined to bring down the fiscal deficit ratio to 4.5 per cent of GDP in FY26; and then presumably to 3 per cent in the three subsequent years, before settling in this region. Hence when the GDP touches $5 trillion, the deficit would be around ₹15.7-lakh crore (against ₹16.5-lakh crore in FY24) assuming deficit at 3.5 per cent and GDP at ₹448 lakh crore in FY28. This would decline further as the 3 per cent norm is attained. What this means is that the level of overall borrowing will also come down.

This means that future expenditures have to be aligned with these levels of borrowing while working on the assumption of limited buoyancy in revenue growth. A lot of the gains in the last few years under conditions of muted nominal growth in GDP is due to better coverage and compliance.

Multi-dimensional poverty

And then there is another aspect distinct from the GDP and fiscal numbers but critically interlinked with the two. This is the NITI Aayog concept of multi-dimensional poverty. The institution has calculated poverty in a novel way where, interestingly, income does not feature. This is a radical change from the generally accepted rule of income that is proposed by multilateral agencies.

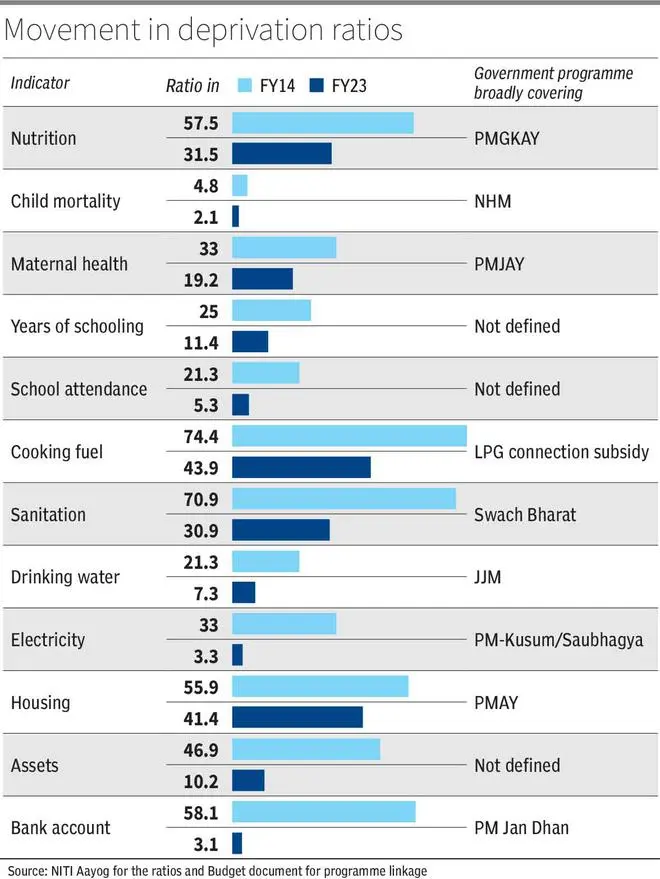

It instead looks at 12 indicators and then sees what proportion of the population is deprived of these benefits. In case they fail in more than one-third of the indicators then they are classified as multidimensionally poor. The indicators are nutrition, child mortality, maternal health, access to schooling, school attendance, cooking fuel, sanitation, water access, power, housing, assets and bank account. The concept is hence broad and looks at access to a number of essential services/goods. The poverty ratio for the nation has came down from 29.2 per cent to 11.3 per cent between FY14 and FY23.

Now, the important thing is that for most of these amenities/facilities that are covered, the role of state is important. This is so because the Centre, in particular, has certain aggressive programmes that ensure delivery of these services. The Table tries to map the movement in the deprivation ratios under each of these indicators (the extent of deprivation in each indicator) along with the Central scheme that is meant to address these deprivations.

The conundrum is that going ahead, can the Budget funds be used to finance all these programmes? In general, given the high levels of deprivation in the country at the start of the middle of last decade, the government had two options. Do we bring about growth and wait for the trickle-down or address issues at the grassroots directly?

As time was of essence the approach was quite radical where direct benefits were provided through a plethora of programmes to alleviate the conditions of the poor. Hence there has been remarkable progress here as in 9 of these 12 elements a large role has been played by the state. The fragile condition of the lower income groups can be gauged by the fact that even today 800 million people are dependent on government for the supply of free foodgrains. Counter-intuitively it can be argued that if there was no direct intervention by the government, this improvement in multi-dimensional poverty indicators would not have been achieved.

Now with the economy moving ahead at a rapid pace, in the next 5-7 years there will be real growth which should ideally address the issue of creation of more jobs so that the people are able to handle their own affairs and are less dependent on the government for direct support. The government has shown its resolve to lower the fiscal deficit ratio and this can be taken as given. This could mean that a lot of these development programmes will have to be either lowered in scale or financed by higher buoyancy in revenue.

Difficult to withdraw

How much of growth is brought about in a broad-based manner across sectors such that employment is generated which enables households to fend for themselves needs to be watched. The observation over the years is that it becomes very difficult to withdraw any development programme and often it is only the allocation which is tinkered with at the margin. Hence intervention in terms of subsidy or direct benefits through cash transfers on LPG cannot be eschewed.

After reaching this far in terms of reduction of the number of people who qualify as poor under the new concept, there is always a risk of people’s well-being slipping in case any of these benefits are withdrawn. MGNREGA is a classic instance where the allocations have just been increasing over time from a modest ₹15,000 crore to over ₹1-lakh crore during the pandemic; for FY25, the allocation is ₹86,000 crore.

One cannot be sure if there can be any substantial gains in terms of tax revenue with growth in economy being at around 12 per cent per annum in nominal terms and a largely unchanged tax structure. Creating jobs with sustainable income streams is the only way out.

The writer is Chief Economist, Bank of Baroda. Views are personal

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.