‘In life always account for variable change!’ This quote from the movie 21 , underscores how if we fail to factor for moving parts in a product that has numerous variables, chances are high that we may get caught on the wrong foot.

Things are simple when variables are fewer. For example, take the case of picking stocks based on PE-based valuation. If a stock A has an EPS of ₹10/ share and is trading at ₹100, then it implies the PE ratio is 10 times. The variables determining the price here are EPS and PE ratio. If you increase one variable PE ratio to 20 times believing it to be the fair multiple, the stock is worth ₹200, well above the current price of ₹100. This is assuming the EPS will stay at 10 and not fall to, say, ₹5 or zero in future. Missing the scope for change in any of the variables can trap you. If this is the case in a product with two variables, what are the possibilities in a product with more variables?

Valuing the business

This brings us to Enterprise Value or EV-based approach to picking stocks. Enterprise value refers to total value of a company/business. This total value as perceived by the market is represented by the sum of its market cap and net debt.

Typically, EV-based multiples that are used to value stocks are EV/EBITDA, EV/EBIT, EV/Tonne, EV/Sales, EV/subscriber, etc. The most common amongst these is EV/EBITDA, which is sometimes preferred over PE to value businesses that typically require debt and regular capex — telecom, cement, steel, etc. In such cases, the value of stock or its market cap is arrived at by giving the business a multiple linked to EBITDA and then adjusting that for net debt in the balance sheet – ie Market cap = EV minus net debt or Share price = EV/share minus net debt/share. Here EV = EBITDA *multiple (times)

So as you change your valuation approach from price to enterprise value, the number of variables changes — EBITDA, Debt and EV/EBITDA ratio in this case. But the interesting thing to note here is that, even if two out of these three variables do not change much, the implications to the stock price can change widely.

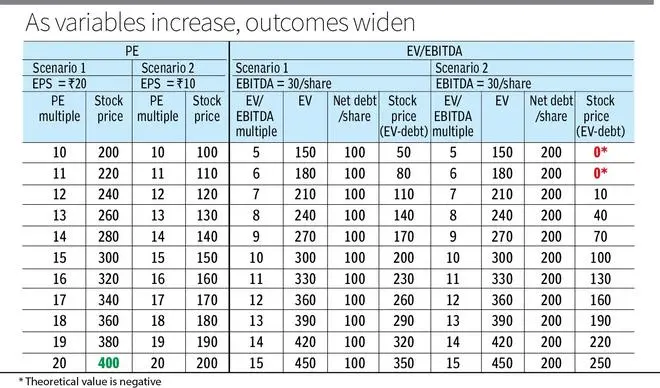

Using the same example of company A above, let us add another element to it. Let us assume two scenarios – Scenario 1: Stock A has debt of ₹100/share, wherein EBITDA is 30/share; Scenario 2: Stock A has debt of 200/share, wherein EBITDA is ₹30/ share. It is important to note here that while PE of a stock can change based on debt and corresponding interest paid, EBITDA will remain the same. For simplicity’s sake, let us assume the rate of interest is 10 per cent and tax and depreciation are zero. In this case, under scenario 1, the EPS will be 20 per share, while it will be 10 per share under scenario 2. Let us look at the range of outcomes that are possible in arriving at the share price.

The illustration below explains how the value of a stock can change as just one variable changes.

Depending on assumptions you make, the stock of A can be valued from zero to ₹400. You can further increase the multiples and make the valuation range even wider.

What if more variables can change according to different scenarios? What if debt can be converted into equity? What if selling price is increased or decreased, which can have outsized impact in increasing or reducing EBITDA versus current levels? The outcomes will also expand wildly on either direction.

There are times when fundamental valuation exercise, which involves assessing different variables with different possibilities, will involve some levels of speculation. As Benjamin Graham says, – ‘ some speculation is necessary and unavoidable, for in many common stock situations there are substantial possibilities of both profit and loss, and the risks therein must be assumed by someone.’

But he goes on to caveat that with, ‘But there are many ways in which speculation may be unintelligent. Of these the foremost are: (1) speculating when you think you are investing; (2) speculating seriously instead of as a pastime, when you lack proper knowledge and skill for it; and (3) risking more money in speculation than you can afford to lose’

As the variables increase, like when you move from PE ratio to EV/EBITDA and then to EV/Sales, while investors can diligently remain within the boundaries of core fundamental analysis, the risks of straying away from pure fundamental analysis into unintelligent speculation increases. Investors need to take cognisance of this.

Why this topic now?

It is due to the recent buzz around Vodafone idea, and the extremely broad range of price targets on the stock from sell side analysts following the FPO, based on various assumptions and changes to variables. There has been a wide range of assumptions from EV/EBITDA multiples, estimated EBITDA, debt conversion into equity (and at what price), scope for cancellation of AGR dues partially, etc. Some assumptions are required, but have they been reasonable?

Hence we wanted to highlight factors that investors need to consider while using the EV/EBITDA multiple in general, and possibilities that one can stray into unintelligent speculation unknowingly when it comes to valuing Vodafone Idea.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.